the multimedia paradox

The Multimedia Paradox AND The Message vs. The Messenger

The Multimedia Paradox

By Tad Simons

From time to time – particularly during those periods in the school year when teachers and administrators are filling out their budget requests or grant applications – we here at Presentations magazine get frantic calls from frustrated educators trying to locate hard, irrefutable, empirical data supporting the notion that technology improves learning outcomes in the classroom. Unfortunately, we then have to share an ugly and somewhat mystifying truth with these good folks: Though there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that multimedia technology is a boon to learning and teaching, there is precious little objective, scientific evidence to support the claim.

The fact that relatively little empirical research exists for such a widely accepted belief is mystifying because the questions seem so simple. Do kids learn more when there are computers in the classroom? Does material projected on a screen teach better than text and pictures in a book? Are PowerPoint slides more effective than a felt-tip marker scribbled on a sheet of acetate or words from a book?

How difficult can it be to answer such basic questions?

Separating the medium from the message

Extremely difficult, as it turns out. When common sense smashes headlong into science, things can get very messy, very fast. Take that last question about the efficacy of PowerPoint slides versus text in overhead or book form. First, you have to define what a PowerPoint slide is. Is it text in bullet points? If so, how many? Text only, or text with images? If the latter, what is the ratio of text to graphics? What kind of graphics are we talking about – an illustration, chart, clip art? Do the slides include animated transitions? If so, what kind, and how are they designed? Is the material being presented on its own or with the aid of a presenter? If it’s the latter, how do you make sure the information is presented exactly the same way in each round of a study – that each syllable in the presentation is stressed in precisely the same way? If there is a presenter involved, and tests results fluctuate, how do you differentiate the effect of the presenter from the effect of the presentation media? And if technologies such as projectors and document cameras are primarily delivery systems for various forms of content, how do you differentiate the effect of the technology from the quality, or lack thereof, of the content?

This is just a small sampling of the issues Presentations editors ran into when we conducted our own study in 2000 in partnership with 3M – and, candidly, we were not able to resolve them all. It turns out not to be entirely our fault, however. Indeed, the reason there isn’t much reliable scientific research in the area of multimedia technology’s effect on learning is that the people to whom we would normally turn to for concrete answers to such questions – educational psychologists, social scientists, media researchers, etc. – have, as a group, pretty much concluded that when it comes to using presentation technology to deliver a message, it is practically impossible to separate the medium from the message, or from the messenger. In the words of Richard E. Mayer, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, “It is not possible to determine whether differences in what students learn from text-based versus computer-based presentations are caused by the medium or by the content and study conditions, which are inseparable from the medium."

In other words, the medium (technology), message (content) and the messenger (presenter or teacher) are inextricably linked.

Multimedia learning

Fortunately, Mayer didn’t give up there. He has spent much of his academic career studying the effects of multimedia and technology on learning, and has produced one of the most scientifically rigorous books available on the subject, Multimedia Learning (Cambridge University Press, 2001), which was recently reprinted in paperback. The culmination of 10 years of research, Mayer’s book deserves a much wider readership than it has gotten to date, for it contains some of the most convincing research available on the effectiveness of using multimedia in the classroom.

Among Mayer’s findings: when certain types of material are presented using multimedia methods, retention (defined as the ability to recall facts or steps in a process) increases by an average of 23 percent; when text and graphics are combined, retention goes up an average of 42 percent; and if the text of a presentation is spoken rather than read – if students hear the words, rather than read them – retention goes up an average of 30 percent.

More important is Mayer’s research involving what he calls the “transfer" of information, or the ability of students to integrate the information into their already existing knowledge base and use it to generate ideas or solve abstract problems (i.e., the ability to understand and use the information). The jaw-dropper in Mayer’s research is that students tested on their ability to “transfer" information that had been presented to them multimedia-style showed a whopping 89 percent improvement in performance over traditional book-based methods. Broken down into categories, when text and graphics were combined in a teaching presentation, the students’ transfer ability went up 68 percent; when the information was presented orally rather than read by the student, the transfer rate went up 80 percent.

Here comes the paradox

That’s amazing, you say. Those are the kinds of numbers I’m looking for! And indeed they are, especially if you are trying to make the case that learning outcomes in the classroom are improved by the use of multimedia – as anyone must do if they are applying for Title II D technology funds available through the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001. (For more on the NCLB Act, see the September feature article, “No nickel left behind.")

That’s the good news. The bad news for people in search of scientifically irrefutable numbers to hang a grant or funding request on is that Mayer’s research also suggests exactly the opposite – that multimedia can actually have a detrimental effect on a student’s ability to learn, and in some cases, a colorful slide with eye-catching graphics can be less effective than a paragraph in a book.

Indeed, Mayer’s ultimate conclusion is that while a little multimedia may be a good thing, too much multimedia is often a bad thing. For example, although Mayer’s research shows that information retention and transfer improve when an animation or illustration is accompanied by narration (from a teacher, say), retention and transfer both go down if the narrator’s words appear on the slide at the same time (e.g., when a presenter reads bullet points from the slide). Furthermore, Mayer’s studies show that, paradoxically, while some animation and graphic support may improve a student’s ability to absorb a message, too much of it, in the form of extraneous movement, sound or text in a multimedia presentation, can severely diminish its effectiveness. When it comes to multimedia and learning, it turns out that less is actually more.

Avoiding the technology trap

For anyone crafting an ironclad argument for investing in presentation equipment, such apparent contradictions can be vexing. But appreciating the nuances of Mayer’s research should be an essential goal for anyone who wants to formulate a coherent rationale for purchasing multimedia technology. Because in order to account for results that, on the surface, seem to contradict themselves, Mayer and other researchers are in the process of developing a new intellectual framework for discussing the efficacy of multimedia in the classroom – one that embraces both the technology and the people using it.

To understand this framework, at least two important distinctions should be made. First, according to Mayer, the problem with asking such questions as “Are computers good learning tools?" or “Does technology help or hurt in the classroom?" is that these are questions that focus on the technology, rather than the education content the technology is delivering. Such questions are inherently flawed, says Mayer, because they emphasize the “power" of technology over the needs, preferences and abilities of the people using it. The same mistake has been made with other promising technologies, he points out: “Film, radio, television and computer-assisted education all produced the same cycle." All of these technologies came with grand promises to revolutionize education. These promises were followed by a rush to implement the new-fangled technologies in schools and, decades later, the obvious conclusion is that these initial “hopes and expectations went largely unmet." Mayer warns that computers, projectors, document cameras, whiteboards and all the rest are now caught in a similar cycle of technological infatuation. However, he also proposes a way to avoid falling into this same trap. The historical problem with focusing too much on the technology, says Mayer, is that “instead of adapting technology to fit the needs of human learners, humans were forced to adapt to the demands of cutting-edge technologies." The solution, he says, is to adopt a “learner-centered" approach to multimedia that is “consistent with the way the human mind works."

What is ‘learning’?

There is no grand consensus on how the human mind absorbs and assimilates information, of course, but Mayer has his suspicions. The problem with technology-centered methodologies, he says, is that they treat information and knowledge as quantifiable commodities that can be passed from teacher to student like a bucket being filled with sand. In this view, there is no qualitative difference between words and images; they are just different ways of freighting information, delivery containers that can be transferred from teacher to student in a more or less mechanical manner.

In terms of learning, Mayer makes a crucial distinction between such mechanical retention (the ability to remember and regurgitate facts) and understanding (the ability to integrate new facts with what you already know, then extrapolate new ideas or concepts based on that information). For Mayer, understanding is the preferred outcome, because it ultimately leads to knowledge, which is the ultimate goal of education. Furthermore, Mayer believes, because human beings receive and process information through two basic channels, verbally and visually, the advantage of using multimedia is that it “takes advantage of the full capacity of humans for processing information." Understanding, the higher form of information processing in Mayer’s view, “occurs when learners are able to mentally integrate and make meaningful connections between visual and verbal representations." Mayer calls this the “cognitive theory of multimedia learning."

What’s the big idea?

For teachers and administrators trying to make a case for investing in such modern niceties as computers and projectors, the big idea at the center of Mayer’s research is that, when used correctly, multimedia both improves information retention and understanding (that higher-quality form of learning that leads to knowledge). Incidentally, Mayer’s research also shows that instruction conveyed using multimedia helps students at the less-proficient end of the educational performance spectrum – a disproportionate number of whom are in Title I schools eligible for NCLB funding – more than those at the higher end.

The trouble is, citing Mayer’s research or anyone else’s, one can’t simply declare outright that multimedia is an unqualified boon to the teaching profession. Because when the wheat is separated from the chaff, whether multimedia instruction is good or bad depends almost entirely on those who design the multimedia materials and those who teach with them.

As compelling as his research on the potential benefits of multimedia in the classroom is, Mayer also has plenty of research suggesting that poor use of multimedia may be worse than no multimedia at all. Too many bells and whistles on a PowerPoint slide can overload the auditory and visual channels, says Mayer, diminishing a person’s ability to understand the information it presents. Likewise, extraneous graphics, sounds or animation – elements that do not relate directly to the core message of a slide – can distract and fragment a student’s attention rather than focus it. Depending on how the presenter or teacher incorporates multimedia into their message or lesson, it can help facilitate the understanding mode of learning, or work against it.

As it turns out, multimedia technology is the neutral part of this information-transfer equation, so how we choose to use it makes all the difference in the world. Unfortunately for those who crave the certainty of science, the quality of the content and the skill of the person presenting it are devilishly tough intangibles to isolate in the lab. That won’t stop scientists from trying, but it may explain why they could have difficulty succeeding.

Tad Simons is editor-in-chief of Presentations magazine.

Originally published in the September 2004 issue of Presentations magazine. Copyright 2004, VNU Business Media.

Found at presentations.com

Why multimedia researchers have a tough time dealing with people

Podium

By Tad Simons

Those who need to justify the purchase of presentation technology with concrete data proving that the new technology represents an improvement over the old frequently run into a perplexing problem: very little such data exists. Certainly, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence suggesting that projectors, whiteboards, document cameras and the like provide a more vivid, engaging and ultimately more productive teaching experience. (Teachers all over the country can tell you how these tools have transformed their classrooms into busy hives of interactive curiosity.) But if you’re hunting for irrefutable scientific proof that these technological tools work as advertised, don’t be shocked to discover that most science on the subject isn’t much help.

Message vs. the messenger The reason for this, as we report in our story “The Multimedia Paradox," is that it is extremely difficult to separate the media or medium (PowerPoint, video, flip charts, etc.) from the quality of the content, in both concept and design, and the skills of the presenter or teacher using it. After all, two different presenters can use the exact same media and deliver two entirely different presentations – one boring and ineffective, the other fascinating and inspiring. Likewise, two different people in an audience can experience the exact same presentation and react to it in opposite ways, depending on any number of factors, including their age, education, background, values, personal preferences, learning style and frame of mind at the time of the presentation. (How late did that party go last night, Brad?)

People are the problem. For research purposes, scientists have a difficult time recreating the true circumstances of a presentation or classroom largely because people are involved, and people are notoriously unpredictable and inconsistent. No two presenters are alike. No two teachers present material the same way, and even the same teacher delivering the same material varies their delivery every time. In the lab, consequently, a seemingly straightforward question such as, “Are PowerPoint slides a better teaching tool than flip charts?" quickly spawns an aggravating swarm of qualifiers: For whom? Under what circumstances? Using what content? In what manner? “Better" in what way? It doesn’t take long for a conscientious scientist to realize that such questions are essentially unanswerable, like asking, “Were van Gogh’s paintbrushes better than Picasso’s?"

The key to it all

And yet, the overwhelming consensus from those who use these tools on a daily basis is that they do in fact improve learning, retention and engagement, and in many cases they act as a transformational catalyst for the vital communication between teacher and student. The unfortunate conundrum is that presentation technology does not work its magic for everyone in the same way, and in some cases it doesn’t work at all.

There is however a way to ensure that the technology delivers on its promises. Science won’t tell you this, but those who believe in the technology and have experienced success with it all say the same thing: purchasing a projector, electronic whiteboard, or any other device is only the first step. The second most important step toward getting the most out of a presentation technology purchase is properly training the people who are going to be using the technology. That’s why 25 percent of any given technology purchase under the No Child Left Behind Act is designated for training. Because without training, the likelihood that the technology will be misused, damaged or completely ignored skyrockets. Proper training up front and continuous user education over the life of the product is, quite simply, the key to it all.

The final solution

In the lab, people are the problem because they introduce variables that can’t be isolated or accounted for. But in real life, these variables are precisely what make the latest presentation and communication technology so powerful. All any new technology really does is open up a host of possibilities that didn’t exist before, and it is up to us, the people employing this technology, to make the best possible use of it. When it comes to presentation technology, its effectiveness or lack thereof ultimately depends on human beings, the presenters or teachers using the technology to command listeners’ attention and orchestrate an exchange of information. The ineffable but essential factor that makes it work, or not, is the quality and intelligence of the media, and the skill and knowledge of the presenter.

Tad Simons is editor-in-chief of Presentations magazine.

Write to him at tsimons@presentations.com.

Originally published in the September 2004 issue of Presentations magazine. Copyright 2004, VNU Business Media.

Posted on December 28th, 2015

Hour or Code

Posted on December 14th, 2015

restore deleted events in Google Calendar

Posted on November 17th, 2015

hidden gems

Posted on November 8th, 2015

remind

Remind is a communication tool that helps teachers connect instantly with students and parents. Send quick, simple messages to any device.

Posted on November 6th, 2015

flubaroo

Teachers, do you…

Not have enough time for grading?

Want useful measurements on student performance?

Need a free solution to help?

If so, then Flubaroo can help!

Grade online assignments in under a minute!

Get reporting and analysis on student performance!

Email students their scores.

Posted on November 6th, 2015

video apps for chromebook

Posted on November 2nd, 2015

keyboard shortcuts

Posted on October 30th, 2015

hypderdocs

Co-creator of HyperDocs Lisa Highfill explains it this way:

HyperDoc is a term used to describe a Google Doc that contains an innovative lesson for students—a 21st Century worksheet, but much better. The name is one that Sarah Landis and I made up—it’s about hyperlinking your docs for amazing learning experiences!

With one shortened link, students can access a lesson that contains instructions, links, tasks, and many clever ways to get kids thinking. Focusing on creating opportunities for choice, exploration, and ways for kids to apply their knowledge is key to creating a truly innovative HyperDoc.

Multimedia Text Sets

A multimedia text set is a collection of lessons, various texts, and resources based around a topic or theme. It can be an amazing tool to build background knowledge, shift pedagogy to exploration of content rather than lecture, or even a tool to flip lessons. HyperDoc lessons can be a part of a Multimedia Text set one of the options to choose from in a table.

Wanna see some HyperDoc examples? Give one a try in your classroom, or create your own!

Posted on October 30th, 2015

all the fonts!

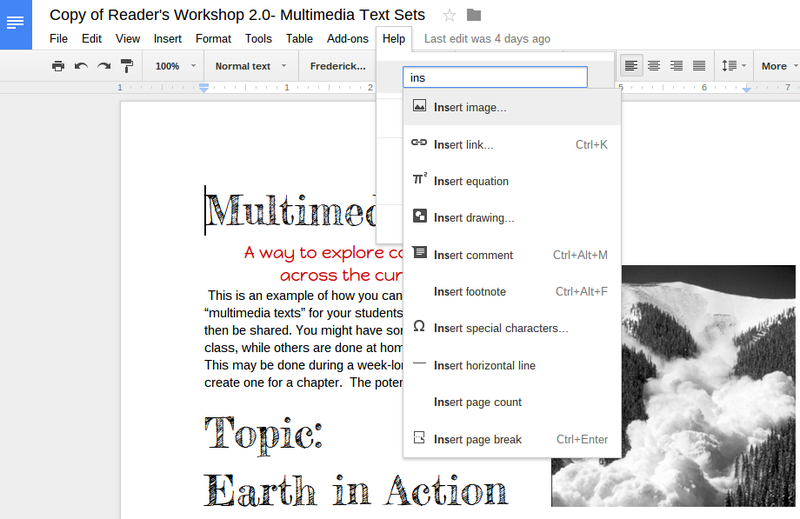

- Open any Google Document, or create a new one

- From the Add-ons menu click Get Add-ons

- In the Search Add-ons box enter “Extensis Fonts"

- Select the Extensis Fonts add-on from the list

- Click the Free button in the upper right hand corner

- Click Accept to install the add-on to your Google Docs account

- The Fonts Add-On will now be available for use in any of your Google Documents

Posted on October 30th, 2015